The Secret Sensuality of Trees: Michael Winstone’s Globe-trekking Race to Scan and 3D Print Trees Lost to Deforestation

For the past 20 years, Michael Winstone has traveled the world’s forests to scan and 3D print trees that are in danger of being cut down. His work is currently on display in museums, galleries and private displays around the world. His most famous work is 41°40’00’’N.00°54’30’’W, and other permanent public works include “N1-53-32-8:132º42′.34º45′.JA” in Takamiya, Hiroshima, Japan and “IGN.185: iv.269.904, Coto Redondo, Pontevedra, Spain.”

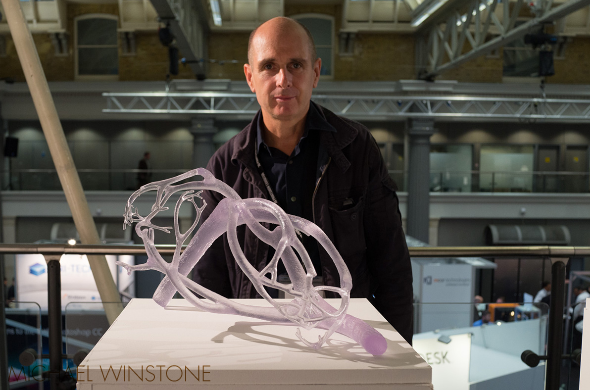

His sculptures feature human-like plant forms and simple fractal elements. These join together to create complex organic-shaped structures that feature “self-similarity” in anatomic texture, body and construction.

Winstone’s 3D printed trees preserves the bark striations and forms of real trees that no longer exist, as well as current trees that may be lost to disease, old age, or ongoing deforestation.

Read on about his life’s work.

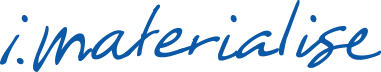

Pictured is Michael Winston, standing beside one of his works during the 2014 London 3D Printshow. Although his work headlined the show and was at the very forefront of the upstairs gallery, Michael preferred to stand apart from his trees so that visitors could focus on them.

“The most beautiful trees are among the most vulnerable.” He notes solemnly.

Michael was born in Toronto in 1958, and grew up on the He grew up on the Isle of Wight and studied Fine Art at Leeds Polytechnic and Sculpture at the Royal Collage of Art. For the past 10 years his studio practice has been based in Madrid Spain, and he’s traveled the world in search of trees to 3D scan and print.

During his travels, Winstone digitally extracts bark data from a specific tree. This forms the surface of his sculptures, and provides a permanent “finger-print” of the tree.

“There is a strong connection between plant and human forms. Human, animal, and plant tissues are generated from substrates. These substrates provide us with nourishment and a place for our roots, our foundation. Environmental forces affect our growth, until we each form into our various beings and functions. Trees have fingerprints, and so do we.”

Michael’s prints are used to create giant tree sculptures, such as 41°40’00’’N.00°54’30’’W. This is a bronze sculpture that towers above skylines at 26 foot (8 meter), and is permanently located in Zaragoza, Spain.

From a technical perspective, his large-scale 3D prints are an impressive feat. 3D scanning trees creates large 3D design files that are several gigabytes in size. The minute detail in their bark and branches overwhelms most mesh repair software packages.

“Currently, Materialise’s Magics is used to prepare these files for 3D printing. We tried other packages, but they could not handle these large file sizes.”

Winstone uses Magics to correct problems that make the file unprintable. Problems could include non-watertight data, fixes flipped triangles, bad edges, and any holes that are inherent in these scans. He may use it to add holes and cuts where needed, or to include serial numbers, ensuring that each fractal-inspired print is a limited edition piece.

3D Scanning the surface of trees creates a unique “fingerprint” of the tree… it also creates an enormous file that most mesh repair software cannot prepare for 3D printing. Michael Winstone’s team uses Magics to repair these large meshes.

There is no doubt that the man understands technology. In fact, he has released “51,5.4728N 0,1.9137E,” an interactive tree video where you can touch and poke at a 3D tree:

However, Michael needs all the time he can save: in the rain forest alone, 2,000 trees are cut down every minute. This means that as you read this, his life’s inspiration is being cut apart, dying of disease, or simply falling apart from old age.

As Michael Winstone speaks, his voice is soft and demeanor understated. He prefers to stand off to the side of his exhibits, rather than in front of them. This mute vigilance is to allow patrons time to connect with his work, and is not out of fear of anyone damaging his life’s work. In fact, a security guard interrupted the conversation to scold Winstone for enthusiastically patting his own sculpture.

This Pagoda tree sculpture, 51°28’55.0”N 0°17’31.1”W., was created from a living tree in Kew Gardens, London, UK. It is part of the “Old Lions” series, featuring the oldest surviving trees at Kew Gardens!

This is the Pagoda tree in Kew Gardens, upon which Michael Winstone based his work, “51°28’55.0”N, 0°17’31.1”W.”

Michael Winstone has bigger concerns than a broken print. He feels that his very inspiration— trees— are overlooked as “ordinary.”

“There is nothing ordinary about trees!” He insists during a flash moment of intensity, “they are sensual, full of life and humanity. Once a tree is destroyed, it is gone forever– there will never be another one quite like it.”

He pats his sculpture again, side-eying the guard, and succinctly draws together the words needed to explain the importance of preserving something many people may overlook.

“This tree you see here no longer exists. Future generations will not get to see it. 3D scanning and printing these trees quite literally preserves our world. Preserving the shapes and detail of these trees for future generations also preserves us… trees are important for humans. I hope that my statues inspire us to better appreciate what is so often overlooked, and to take better care of our natural heritage.”

“There is nothing ordinary about trees! They are sensual, full of life and humanity. Once a tree is destroyed, it is gone forever– there will never be another one quite like it… 3D printing can inspire us to take better care of our natural heritgage.” – Michael Winstone

To ensure that patrons notice the trees, he stands back and fades into the scenery. Taking his nature-first theme one step further, Winstone calls each print after the geographic coordinates of the tree. This emphasizes the tree above all else.

“We often don’t stop to realize what we’ve lost until it’s gone forever. We get excited about limited edition jerseys, but how many of us realize that every tree is entirely unique? If it takes an exhibit to bring people closer to appreciating our natural heritage, then so be it.”

There is a secret in each of Winstone’s trees: each tree represents a family, which includes both heterosexual and same-sex couples.

Trees are at the heart, root, and soul of Winstone’s artwork, but the man is still an artist. When we asked about why he picked trees over other plants, and why he picked certain trees over others, he revealed a startling secret:

“Each tree I pick has human characteristics. The tree itself physically represents one man, one woman, and one child. One part has a graphic male characteristic, another branch contains more feminine, curvy characteristics… and another section has a shorter, less developed appearance of a baby or child. I’ve also included same-sex couples. Each tree I select physically embodies a family. They are sensual, vibrant, exceptionally human trees.”

Michael Winstone’s 3D prints are turned into large, towering sculptures of old or lost trees. For more photos, or to contact him, visit his portfolio site!

Winstone ends the interview with a smile and warm handshake.

He hopes that when people see his 3D printed tree sculptures, they appreciate the unique sensuality and beauty within these “lost trees.” He may well be the only man capable of capturing this fleeting sensuality.

Recommended Articles

No related posts.